Arguing can be seen as aggressive, confrontational and divisive, so most of us, understandably, avoid it at all possible costs. We prefer silence and avoidance to confronting those with different opinions than us.

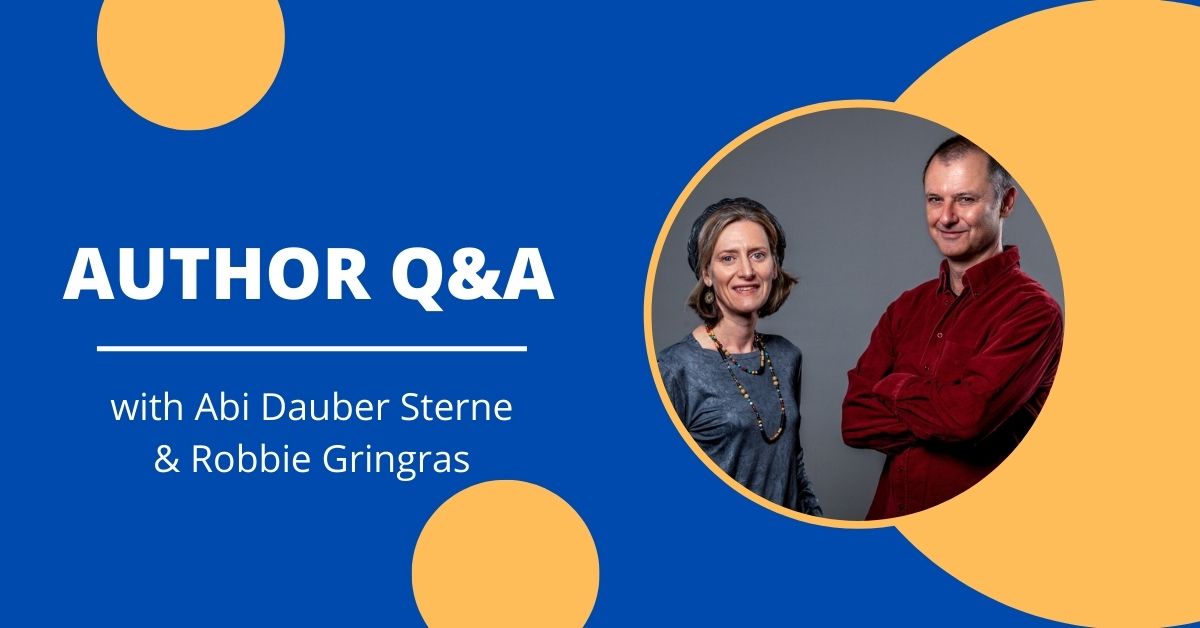

Can there be positive, constructive aspects to arguing? Surprisingly, the answer is starting to become ‘yes’. Just ask Abi Dauber Sterne and Robbie Gringras, two innovative educators, who are embracing the concept of argument to teach about Israel. Together, they have founded For the Sake of Argument, a new educational initiative that teaches others how to to argue constructively and to accept others who have different opinions about controversial issues in Israeli society.

They recently published a new book, “Stories for the Sake of Argument”, a how-to guidebook that includes examples of contentious and common scenarios in Israel, along with background information, discussion points, and more.

I recently had the privilege of speaking with Robbie and Abi about their new venture. It is my hope that their creative use of argument will help bridge social gaps and get us all communicating. (And hey, if a few Knesset members learn a trick or two, it wouldn’t hurt!)

Talking with Educators Abi Dauber Sterne and Robbie Gringras

How did the project start?

The project was an outgrowth of our work with Moishe House, and lockdown. Working with young adults on Israel engagement, we came to two realizations: First, it is impossible for groups of young adults to have deep meaningful engagement with Israel without arguments. Second, young American Jews do not like having live arguments. They avoid them like the plague. So Moishe House offered us the challenge: we need to introduce Israel arguments to people who do not wish to have them. Lockdown gave us the impetus and the opportunity. The impetus came from the need for parents to provide some form of activity around a bored and irritable dinner table that cannot bear any more screens. A classic book by Joel Grishaver was an inspiration. The opportunity came because we were unable to present a huge conference on our Moishe House learnings because of Covid restrictions, and the Jim Joseph Foundation generously encouraged us to redirect the conference funds to developing Stories for the Sake of Argument.

You specifically use the term ‘argument’. Why did you choose that term as opposed to others of similar meaning (debate, disagreement, difference of opinion, etc)?

Three key reasons: 1. As opposed to disagreement, difference of opinion, the word argument implies action. (Disagreement feels more like a state, a description) 2. We want to find room for passion, however potentially destructive it can be. Passion comes from the heart of identity, and a disagreement without one’s identity being involved can be sterile and insignificant. 3. Sometimes euphemism is of value, but sometimes it can engender a lack of courage. We chose the word argument to avoid euphemism and to try to be brave.

What is your vision of a healthy argument?

We see three “families” of dispute. The debate, where my aim is to convince. The negotiation, where my aim is to find a resolution that all agree to. A healthy argument might use the techniques of debate and negotiation, but its aim is educational. Arguments make us think smarter, and give us breadth of perspectives. These are the aims of healthy argument.

As educators, and now authors, why did you choose the genre of storytelling for your book?

These very short stories can be a rich and concise way of distilling a dilemma. In a story, a dilemma becomes a personal challenge rather than an intellectual exercise: Within the fiction there is a real person trying to live their life. In going into the personal, we take a “thin idea” – a concept or a value – and bring it into the “thick expression” of real life where things are more complicated and less pure (Michael Walzer, Thick and Thin). Destructive fights take place in the thin, while constructive discussions take place in the complexity of the thicket. In the Jewish tradition, a short compact narrative invites midrash, a filling in of the gaps. So these stories invite participation and active learning. Finally, stories bring emotion with them, as should good Israel engagement.

Is there a particular age that the book is aimed at?

No – it’s a book that can be used and adapted by groups of all ages.

What sort of exercises do you use to help people build tools to argue better?

The Yes-but principle where you learn to acknowledge you have heard someone (“Yes”), and then allow yourself to disagree with them (“but”); and the non-stick principle when you signal that your opinion does not necessarily represent your entire identity, and thus buy yourself space to think out loud. (“I don’t know whether I fully agree with myself here, but…” “I’m just trying this on…”)

How do you see these skills playing out long-term vis-à-vis how we address issues in Israel?

It’s too soon to tell. We can aspire to change the world, but really these next few years of applied research – generously funded by The Jim Joseph Foundation – will give us a clearer picture.

Stories for the Sake of Argument is now available on Amazon.

Thanks for the post!